“How can my fund ‘lose’ money in a growing market?”

As investors approach the end of each calendar year, attention often turns toward mutual fund capital gains distributions and the potential income taxes the distributions may generate. This is often highlighted by financial publications and media outlets alerting investors about this hazard in the management of their portfolio assets. While most investors would not like to pay any capital gain taxes, this is a component of the investing landscape that is not likely to go away. Correspondingly, Voisard Asset Management Group regularly receives a few questions about mutual fund capital gain distributions, how they are calculated and what impact they may have on a portfolio. Our firm thought you would enjoy an explanation of this normal activity within a mutual fund holding.

The Fundamentals of Capital Gain Distributions

First, let’s cover a few fundamentals about mutual funds capital gains distributions. When your advisor purchases a stock mutual fund on your behalf, you are purchasing a collection of stocks designed to increase in value over the long term. This purchase price represents the market value of all the stocks in the portfolio on the date of purchase, the accrued dividends generated to that date and the value of any holding that has gone up (capital gain) or down (capital loss) in value.

As time progresses, the mutual fund manager may sell one holding in the portfolio for a variety of reasons. This could include a change outlook of the asset, an increase or decrease in valuation, the manager feels that there are better opportunities elsewhere or funds need to be raised to meet shareholder withdrawals. At the point of the sale of an asset, the mutual fund experiences a realized capital gain or capital loss on the holding.

At the end of the year, if the mutual fund experiences a net realized capital gain among all holdings that were sold (gains minus losses), the fund must distribute at least 95% of the capital gains to shareholders. This is required under the mutual fund regulatory structure. In most cases, a mutual fund will complete this distribution once or twice per year, depending on the fund and their internal practices. Many capital gain distributions occur in November and December, but can happen at other times of the year. The capital gains distribution is a taxable event to the fund shareholders unless you own the asset in a tax-deferred or retirement account like an IRA or 401k plan.

The one item that generates the most questions happens to the pricing of a fund when a capital gain distribution is made.

“Walk me through an example.”

As investors receive capital gain distributions, the value of the distribution, the impact on a fund’s pricing (net asset value or NAV) and the cost basis of the fund thereafter create a source of confusion. This is best explained by walking through an example of what share prices and market value at the time of a capital gain distribution. First, let’s assume the following facts:

|

ABC Mutual Fund Facts |

|

|

Mutual Fund Name |

ABC |

|

Date of purchase |

12/1/2012 |

|

Shares purchased |

100 |

|

Cost per share on the date of purchase |

$10 |

|

Cost basis (shares purchased x cost per share) |

$1,000 |

Over the course of the year, the fund manager has diligently performed her job, buying and selling securities for the fund, taking capital gains where necessary and selling assets that have not met expectations. Due to a rising market and the skill of the manager, the share price of the ABC mutual fund on 12/7/2013 had risen to $12, generating a 20% gain for the shareholder of the fund. In the review of realized capital gains and losses generated throughout the year, the manager recognizes a net realized capital gain of $1 per share. As previously stated, the fund company must distribute at least 95% of this gain to its shareholders and does so on 12/8/2013.

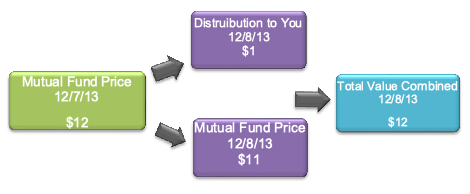

Assuming you receive capital gain distributions in cash (versus the reinvestment of the gain back into the fund), you will receive $100 in the form of a check or a credit to your account (100 shares times $1/share in realized capital gain). On the date of the cash distribution (close of business 12/8/2013), the mutual fund company is effectively taking $1 of share value out of the $12 current price and giving it back to you for your utilization. The share price of the mutual fund on the date of distribution will also decrease to $11 per share. In effect, you still have the full value of the fund at $12 per share. However, it is now contained in two parts which include a share price of $11 and $1 in realized capital gain.

Your cost basis in the mutual fund, outlined above at $10/share, remains the same at $10 per share as this was your original purchase price. The realized capital gain of $1/share that was distributed to you is reported on your income tax returns and the other $1 of gain (unrealized capital gain) continues to be embedded in the share price of the fund. On paper, this series of events would look:

|

ABC Mutual Fund Values |

|||

|

Date |

12/1/2012 |

12/7/2013 |

12/8/2013 |

|

Shares Purchased |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Price on current date |

$10 |

$12 |

$11 |

|

Realized gain distributed |

$0 |

$0 |

$100 |

|

Unrealized capital gain |

$0 |

$200 |

$100 |

|

Fund Value (price x shares) |

$1000 |

$1,200 |

$1,100 |

|

Total Value (fund value + realized gain) |

$1,000 |

$1,200 |

$1,200 |

The total value of the ABC mutual fund is the same on both 12/7/2013 and 12/8/2013, but the composition of the capital gain is different. The difference is that on 12/8/2013 you now have $1 per share of realized capital gain in your possession, $1/share of unrealized capital gain in the fund and a share price that is $1/share lower. The total value remains the same. At this point, you can reinvest the realized gain proceeds back into the fund, reallocate the proceeds to another investment, or receive the funds in a distribution and take your spouse to dinner (always a favorite and a good way to earn brownie points).

“Why did my mutual fund go down 8.3% in one day?”

We often receive this question on the date of the distribution, 12/8/13. In this situation, the investor is seeing the market price of the fund drop from $12 to $11, which represents the

$1/share distribution referenced above and equal to the perceived loss of 8.3% ($1/$12 = 8.3%). In actuality, the fund did not drop in value. On the day after the distribution, the investor has a mutual fund worth $11/share and a realized capital gain distribution worth $1/share, therefore giving your investment a total value of $12/share. The total value of the fund remains the same from 12/7/13 to 12/8/13, however, the composition of the total changed due to the capital gain distribution.

In the example referenced above, we outlined the chain of events that occurred in a capital gain distribution. It is also important to recognize that the same sequence of events occurs when a fund distributes a dividend or investment income. We have the mutual fund distributing a portion of the value of the fund (the dividend) and delivering it to the investor for reallocation.

“My fund lost 30% in one year…We have to get rid of that dog!”

The other question we typically get is the investor who has reviewed the unrealized mutual fund capital gains and losses in their portfolio and sees that a fund has lost a significant amount of value. How can my fund lose 30% when the market was only down 10%? This is not an uncommon situation, especially if in the first year of owning the fund, the value of the fund goes down due to market losses and the fund distributes a realized capital gain during the year. The same chain of events outlined above is working here as well. However, due to the loss in the fund and the capital gain distribution occurring in the same year, the “loss” appears to be exaggerated.

In this case, over the course of the year, the fund manager similarly performed her job of buying and selling securities. However, the market is presenting a tough set of circumstances and the sector has experienced a pullback in prices and market losses. Further compounding the market loss is that some investors have become nervous and elected to withdraw funds from the mutual fund. In order to meet the distribution demands, the fund manager must sell some securities to meet the requests, again creating a realized gain or loss.

“Another example please…”

To help, a second example outlining XYZ mutual fund is warranted. The XYZ mutual fund was purchased for $10/share earlier this year. In this market, the share price of the XYZ mutual fund fell to $9, generating a 10% loss for the shareholder of the fund. The manager is doing her best to navigate the market, but ultimately needs to sell some holdings to restructure the portfolio and meet shareholder requests. In the review of capital gains and losses taken throughout the year, the fund manager recognizes a net realized capital gain of $2 per share. As required, the fund company must distribute this gain to its shareholders.

“How can the manager distribute a capital gain if the fund lost money?”

Recall that when the mutual fund was purchased, the shareholder gained all the embedded mutual fund capital gains and losses in the fund. This can include assets that had been held a very long time, sometimes spanning five, ten or even more years. For example, the fund manager bought the

Widget Company stock in 2002 for a price of $4/share and held it for the last eleven years. During that time, the Widget Company sold their widget’s and increased the share price at a rate of 16% per year, a great investment for the manager. However, business conditions for the company have been a challenge and a new management team has been introduced. The mutual fund manager decides that it is the right time to sell the stock. In looking at the market price, we see that the share price is now $20.47 per share. At the time of sale, the fund manager must recognize a gain of $16.47. This realized capital gain is included when determining if there are any shareholder distributions that need to be made.

In order to show you how this works, let’s assume the following facts:

|

XYZ Mutual Fund Facts |

|

|

Mutual Fund Name |

XYZ |

|

Date of purchase |

6/30/2013 |

|

Shares purchased |

100 |

|

Cost per share on the date of purchase |

$10 |

|

Cost basis (shares purchased x cost per share) |

$1,000 |

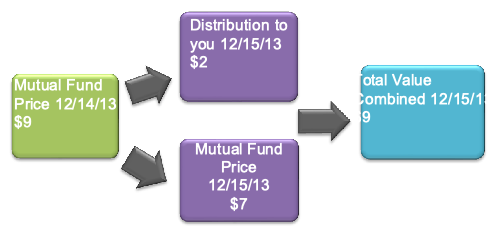

As described, mutual fund XYZ changed in value from the purchase price of $10/share to a current value of $9/share, creating a 10% loss. With the sale of the Widget Company stock described above, along with other sales of securities, the manager is going to recognize a realized capital gain of $2/share and plans to distribute this amount to the shareholders on record.

On the date of the distribution of 12/15/13, the shareholder receives a check or credit to their account in the amount of $200 ($2/share times 100 shares). The mutual fund promptly moves in price from $9 to $7 due to the $2 distribution. In effect, you still have the full value of the fund at $9 per share. However, it is now contained in two parts which include a share price of $7 and realized capital gain of $2.

The cost basis in the XYZ mutual fund, outlined above at $10/share, remains the same at $10 per share as this was the original purchase price. The realized capital gain of $2/share that was distributed to you is reported on your income tax returns and the other $1/share of unrealized capital gain continues to be embedded in the share price of the fund. The investor that is looking only at his capital gain or loss sees a loss of 30%. However, they have neglected to recognize the value of the capital gain that has been distributed. Here, the shareholder has $2 of value per share in cash and a paper loss of $1/share. The fund pricing creates the illusion of a 30% capital loss, when in fact the loss is only 10%.

|

On paper, it looks as follows: XYZ Mutual Fund Values |

|||

|

Date |

6/30/2013 |

12/4/2013 |

12/15/2013 |

|

Shares Purchased |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Price on current date |

$10 |

$9 |

$7 |

|

Realized gain distributed |

$0 |

$0 |

$7 |

|

Unrealized capital loss |

$0 |

$100 |

$100 |

|

Fund Value (price x shares) |

$1,000 |

$900 |

$700 |

|

Total Value (fund value + realized gain) |

$1,000 |

$900 |

$900 |

The capital loss amount is the same on both 12/14/2013 and 12/15/2013, but the composition of the capital loss is different. In this case, your unrealized capital loss is $1/share as this is the change in price from when you purchased the fund to today. The $2/share capital gain, which is included on your tax return, has been distributed to you for utilization or reinvestment.

It may not seem fair that you have to pay the $2/share in capital gains as you have only owned the fund for a relatively short period of time. In effect, you are required to pay a capital gain on the fund today, but will receive the $2/share back in the form of a loss at the time you sell the fund, thus negating the impact of the capital gain distribution.

“Wouldn’t we be better off to reinvest the capital gain?”

While it is true that you can instruct the custodian to reinvest all distributions from a fund, there is no theoretical advantage for the investor to proceed in this manner. The math, while not shown in this paper, will demonstrate the same outcome.

The investor has to look at this chain of events as a set of separate and distinct transactions. First, you purchase the fund for your portfolio. Second, the fund determines that it must distribute a capital gain and sends to you the proceeds either in the form of cash or reinvestment. Third, and at that point, you need to make a separate and distinct decision. Should I reinvest the

distribution into the fund (reinvest), reallocate the proceeds to another investment, or keep the funds for myself?

For the investor that has the distribution reinvested, they are “deciding” to make a subsequent investment in the same fund. They have indicated to the custodian to proceed in this manner and have placed the reinvestment process on “auto-pilot”. This keeps the funds fully invested in the fund, but negates the opportunity to reallocate assets to other opportunities or needs. Each approach is not wrong, just a different way to proceed.

“Do fund managers actively manage capital gains?”

Fund managers are well aware of the income tax ramifications within the assets that they manage and are sensitive to net after tax returns. Throughout the year, many fund managers actively seek opportunities to improve the net after tax return of the fund by evaluating and implementing opportunities to minimize or reduce current capital gain exposure.

Capital gains within a mutual fund and the amount that is distributed to the shareholder work very similar to capital gains on your personal income tax returns. In general, the funds need to recognize and distribute realized capital gains to the shareholder. Capital losses that are realized on an investment can be utilized to offset other capital gains. In the event that losses are in excess of gains, the losses can be carried forward to future years. This process of managing gains and losses works to the favor of the manager who approaches their work in a tax efficient manner.

Since a mutual fund can carry losses forward, we often see capital gain distributions operating in a cycle. In years following market losses (think 2002 or 2008), there may be few, if any, capital gains distributed as the manager is carrying losses forward from previous years and offsetting current gains. As the market advances and more gains are recognized (think 1998, 2006 or 2013), the losses are used up and the fund begins to realize net capital gains. As these gains are recognized, the fund must distribute them to shareholders.

“Don’t Buy The Gain”

Staring in October or November of each year, our friends in the financial press create the usual “Year End Tax planning” issue. The “Don’t Buy The Gain” trumpet is sounded and investors are on high alert. The articles are referencing the situation where an investor buys a mutual fund only to find that a short time later the fund has distributed their realized capital gain. After the gains are distributed, the investor must transfer the gain to their personal income tax return. Recall that this taxability does not occur if the asset is held in retirement or non-taxable account like an IRA or Roth IRA. The taxability only occurs in after-tax, non-sheltered investment accounts. While purchasing a fund and immediately receiving a capital gain (“buying the gain”)

is not a very pleasing event for an after-tax investor, it is also not as bad as it made to sound. Let me explain.

Most investor’s tax returns look very similar from year to year and generally end up in the same tax bracket. If we make this broad assumption, then the distribution of realized capital gains is neutral to the investor. The difference is the timing in the recognition of the gain.

Recall that when you purchase a fund, your cost basis is set at the time of purchase. However, the price of the fund reduces with the distribution of capital gain or income as the investor is given the proceeds for reinvestment. For example, if I were to purchase a fund today at $10/share, then immediately receive a gain of $2/share, the price of the fund would go down to $8/share. If I were to sell the fund immediately thereafter, I would receive $8/share upon the sale and recognize a $2/share loss as my cost basis is still $10/share. The net effect to me as an investor is $0/share ($2/share gain less $2/share loss). This happens regardless of when I purchased or sold the fund as the cost basis carries along with the fund through time.

To assist investors with managing this element of their fund purchases and planning for anticipated mutual fund capital gains, most mutual fund companies begin to distribute estimates starting in early November and extending through mid December. While this can assist you in the later months of the year, it does very little to assist you while purchasing a fund in January or July.

The Voisard Asset Management Group Methodology

The management of capital gains and losses and the impact it has on our clients is important to Voisard Asset Management Group. We monitor and manage a variety of aspects in the selection of the mutual funds held in our portfolio of assets.

First, Voisard Asset Management Group continues to believe that for a majority of investors, the utilization of actively managed mutual funds are the best approach. The mutual fund companies have resources beyond the reach of most advisory firms and employ hundreds of people dedicated to analyzing all elements and components of potential investments.

Second, while we do pay attention to potential capital gain distributions and the impact of taxes, we do not let these factors drive the decision to purchase or not purchase a fund. It is one factor in a wide range of considerations. If we believe a fund purchase is warranted, we will buy it. If the fund warrants a sale, we will sell it.

Third, we do not always know if a mutual fund company will make a capital gain distribution. Over the years, we have been periodically surprised that an estimate provided by the fund company is materially different than expected. Further, a capital gain distribution is not limited to November and December as most are accustomed to expecting. They can and do happen at any time of the year. Therefore, trying not to “purchase the gain” is sometimes difficult to do.

Fourth, Voisard Asset Management Group elects, by design, to receive income and capital gain distributions in a cash payment form. The funds received are credited to the money market

portion of the client’s account. Utilizing this methodology, we can reallocate the distributions to the asset classes that are most appropriate for your individual circumstances or utilize the proceeds for known distribution needs.

Fifth, during our review process of a fund, we evaluate the turnover rate of the fund. The turnover rate of a fund is a decent proxy for how frequently a manager trades his or her portfolio. High turnover is not necessarily bad, but it does have the potential to increase trading costs and may increase the potential taxable distributions coming from the fund. It should also be recognized that some types of funds, like small and micro-cap funds, generally experience higher turnover rates that their large company brethren.

Overall, Voisard Asset Management Group carefully reviews tax situations and events that may directly impact our clients. We take pride in our process and approach to mutual fund investing and continue to work toward making the portfolio assets stronger and more efficient as we evaluate different parameters of each fund we hold.

The Voisard Asset Management Group

Voisard Asset Management Group is a fee-only, independent investment management and financial planning practice located in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Our independent structure ensures that our only financial relationship is with our clients, allowing us to provide unbiased advice, free from conflicts of interest. Our experienced team of financial planning and investment professionals include individuals who carry the Certified Financial Planner™ designations and other industry professional titles.

Our goal is to craft a strategy that is appropriate for you. We simplify the complex and emotional nature of investing into a disciplined approach through a process of open and ongoing communication and a firm understanding of your objectives. We appreciate the continued trust and long-term commitment our current clients place in us. If you feel you are lacking this type of relationship with your current advisor, we invite you to come in for a conversation.